RACIALLY RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS

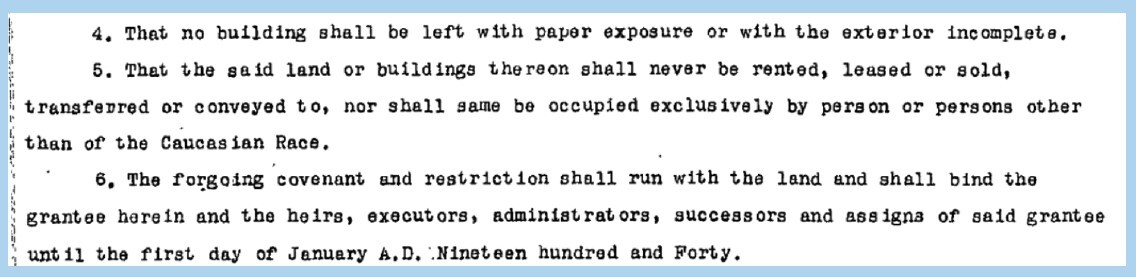

Racially restrictive covenants are “private contracts between individuals that allow them to dictate to whom they’ll sell their property.” Racial covenants restricted or forbade property transfer to anyone who wasn’t White, including but not limited to those of Chinese or Japanese descent, as well as Jewish and Black Minneapolis residents. Researchers with the Mapping Prejudice Project found that 100% of the racially restrictive covenants were targeted at Black Americans.

From the 1910s to 1940s, housing covenants intensified and pushed most Black residents into “less desirable” areas of the city, decreasing their property values. Racial antagonism and violence were used to push Black people and other people of color out of certain communities and into what became redlined areas.

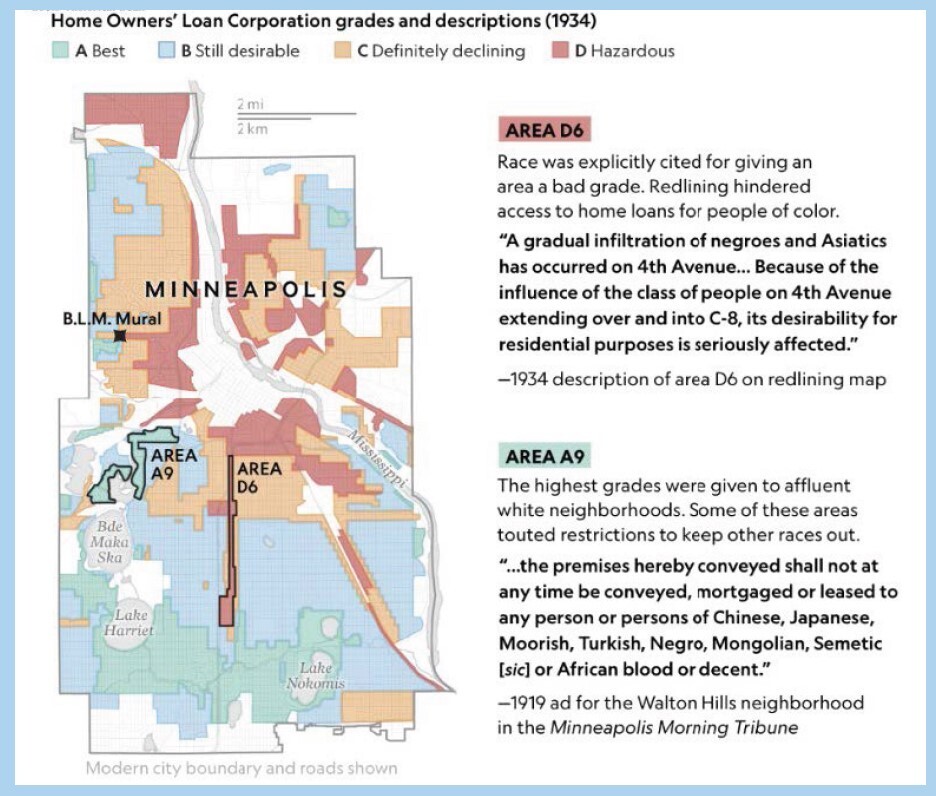

REDLINING

Redlining was a practice used to reduce wealth building among African Americans and people of color by selectively blocking home financing and/or home purchases by race. “Banks used the concept to deny loans to homeowners and would-be homeowners who lived in these neighborhoods. This in turn resulted in

neighborhood economic decline and the withholding of services or their provision at an exceptionally high cost.

OVERCROWDING

Overcrowdedness is defined as more than one person per room. A 2013-2017 American survey showed that Hennepin County residents experience more overcrowding than the average for the region. 8.66% of Black households, 7.15% of Asian or Pacific Islander households, 4.15% of Indigenous households, and 0.65% of White households experience overcrowding. Latinx households experience the highest levels of overcrowding at 18.98%.

I-94 AND I-35W DEVELOPMENT

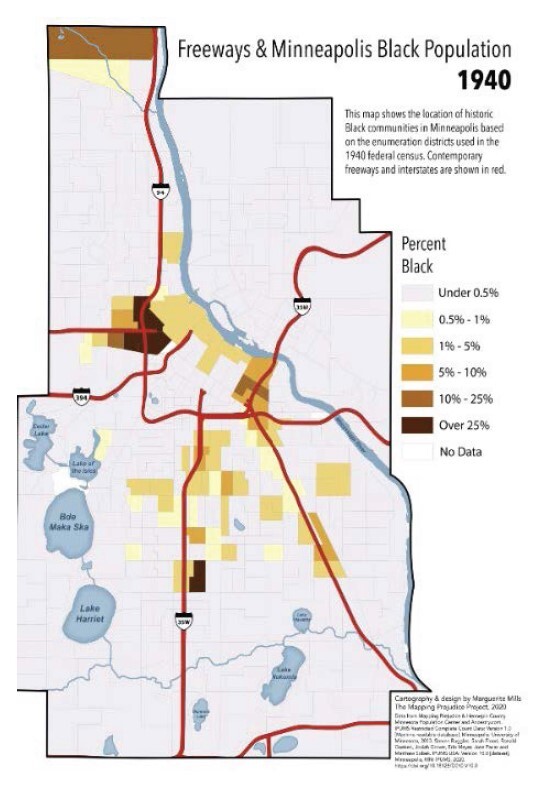

Construction of the Interstate Highway System began in the late 1950s throughout the Twin Cities metro area. In Minneapolis, the business interests of the University of Minnesota and the Downtown area had considerable pull on where I-94 would enter Minneapolis across the Mississippi River. Anyone who voiced their concern over the development with enough fervor could halt the project in a particular area.

With high demand from powerful stakeholders, engineers could move their work to another site and create pressure under which many dissenters folded. Freeways were built through areas densely populated with Black residents by design—Black and low-income residents were known to be less able to push back on freeway development. White-dense communities resisted freeway incursion.

1969 through the early 70s brought about sweeping changes to social and environmental policies. Highway development was forced to respond to these changes, two of the most notable being 1969’s National Environmental Protection Act and the Department of Justice’s 1974 ruling forbidding funding of federal programs that proved to be discriminatory in accordance with the Civil Rights Act. “If such a measure had been in effect during the planning for I-94 between Minneapolis and St. Paul, there may have been a different alignment or a more protracted dispute.”

LASTING HEALTH EFFECTS

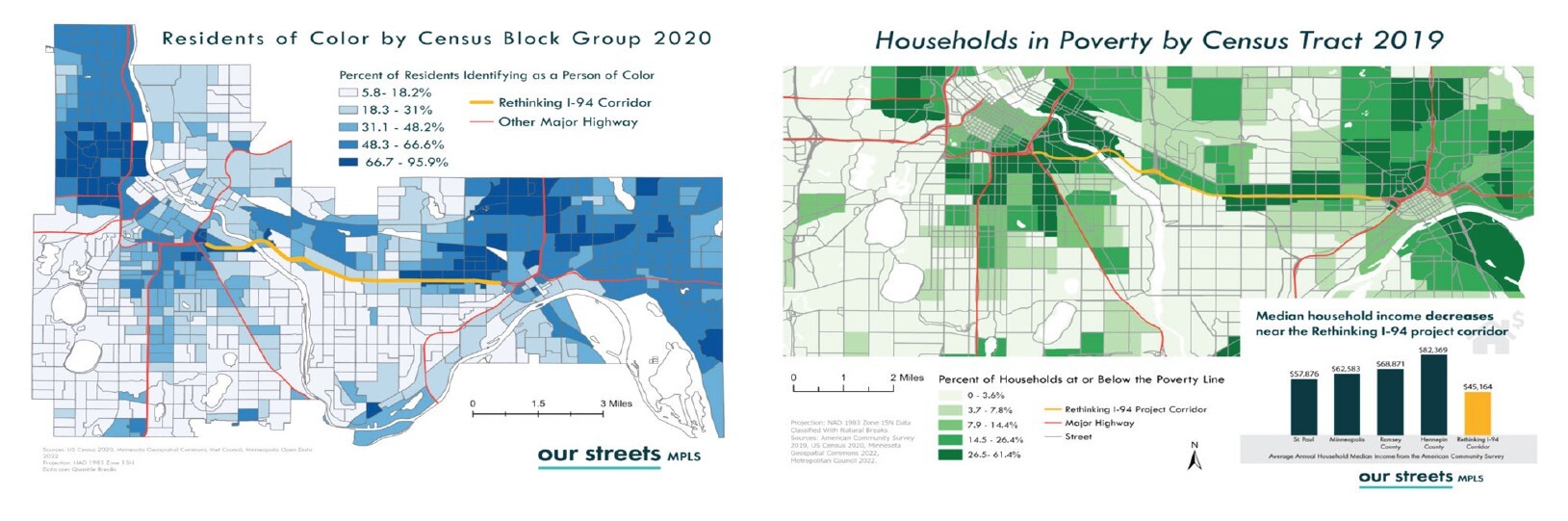

As seen in the maps below, people of color and households in poverty are still more likely to live near a freeway than other residents, which has been, and continues to be, associated with a variety of negative consequences including increased health problems due to air quality impairment. Neighborhoods in close proximity to freeways, such as Elliot Park and the Near North side of Minneapolis, face the greatest exposure to transportation pollution and harmful air quality.

Chronic exposure to pollution can cause increased death rates attributed to cardiovascular diseases and has been linked to lung cancer, reproductive and developmental harm, diabetes, and dementia. In children, high exposure to pollution has been linked to slowed lung function growth and the development of asthma. Roughly 2,000 to 4,000 people die in Minnesota annually due to air pollution-related illnesses. Pollution isn’t a uniquely Minnesota issue; communities of

color are disproportionately exposed to pollution across the United States.

FINANCIAL WELLNESS & HOMEBUYER SERVICES

Through CAP-HC’s Financial Wellness and Homebuyer Services programs, people with lower incomes learn skills for money management and asset building and future homebuyers get support as they prepare to purchase a home. Asset building, including homeownership, is an important way families can lift themselves out of poverty and pass on wealth to future generations.

LEARN MORE

caphennepin.org/financial-wellness

caphennepin.org/homebuyers

Sources: Mapping Prejudice Project; Mapping Inequity; National Geographic; MNopedia; Diversity of Gentrification: Multiple Forms of Gentrification

in Minneapolis and St. Paul; 2000 Census and 2011-2015 ACS; Politics and Freeways: Building the Interstate System, Twin Cities Fair Housing Analysis

by County; State of Asian Pacific Minnesotans; I-35 Disrupted Minority Community, Boxed-in Phillips; Twin Cities Boulevard; Minneapolis 2040; East

Town Minneapolis; Union of Concerned Scientists; American Association for the Advancement of Science